Exhibition on Anton de Kom’s second life, which began in Leiden

Few people would associate the name Anton de Kom with Leiden. Yet the Surinamese freedom fighter is the subject of an exhibition at Museum De Lakenhal. Almost a quarter of a century after his death in 1945, members of the Surinamese Student Union in Leiden plucked him from obscurity. An exhibition titled ‘I Will Fight - Anton de Kom and the Surinamese Student Union’ will continue the rehabilitation of De Kom’s reputation in the Netherlands in 2023.

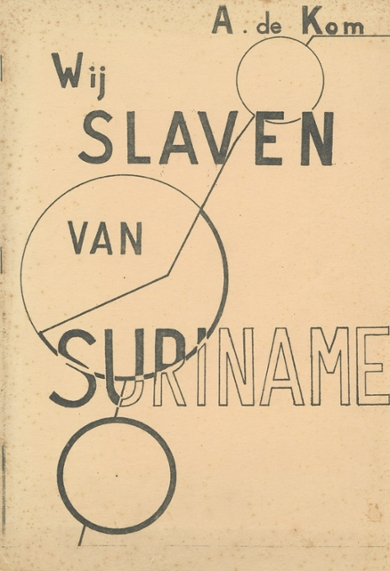

‘This had to be a Leiden affair’, Garrelt Verhoeven of the Leiden University Libraries says firmly. The rediscovery of De Kom had taken place in the Leiden University Library, where Rubia Zschüschen unearthed the first edition of the anti-colonial manifesto We Slaves of Suriname (1934) in 1967. De Kom was the first to describe the history of Suriname through colonised eyes. Zschüschen (who died in 2002) was astonished by her discovery. Even before World War II, De Kom had articulated what Surinamese students in Leiden felt and thought. Verhoeven: ‘Anton de Kom fought against domination and slavery.’

Pirate edition

The activist students urged the Amsterdam publisher Contact to reprint the freedom fighter’s writings. The publisher saw no point in doing so, but De Kom’s widow in The Hague gave the students manuscripts. They then mimeographed their own version of We Slaves of Suriname.

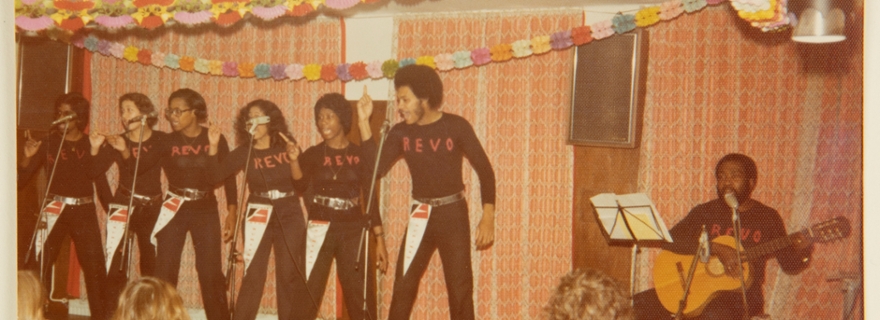

Verhoeven explained that the mimeographed reprints of De Kom’s ideas ‘spread like wildfire’ through the country, including the then overseas kingdom of Suriname. The Suriname Student Union was an offshoot of the Suriname Student Association, which was mainly known for the parties it organised. According to Verhoeven, the union was more militant and politically engaged and, like De Kom, leaned to the left. ‘They fought against injustice and discrimination, as did groups in other countries in the 1960s. But the Suriname Student Union was not involved in Suriname’s independence, which came about in 1975.’

A hodgepodge

Verhoeven emphasises the diversity of the scores of Surinamese people who studied in Leiden in the 1960s. ‘The community, like Suriname, was a hodgepodge. Incidentally, Anton de Kom himself took up the cause of all the groups of people living in Suriname, such as descendants of slaves, contract workers, maroons, Chinese and Hindustani.’

For the exhibition by the Surinamese Student Union, the Leiden University Libraries and Museum De Lakenhal, Henna Goudzand Nahar conducted historical research on the Surinamese Student Union and the pirate editions. The organisers named the exhibition after the title of the poem ‘I Will Fight’.

Zealous copying

Verhoeven notes that De Kom was not only a freedom fighter, but also a gifted writer. But without the zealous reproduction of his work by politically engaged Surinamese students in Leiden, it would have remained obscure. One hundred and sixty years after the Netherlands officially abolished slavery, both Anton de Kom and the students who rediscovered his work are in the spotlight in Leiden.

The exhibition on Anton de Kom and the Surinamese Student Union runs from 10 November to 7 July at Museum De Lakenhal. Alongside historical objects, it includes a documentary by filmmaker Emma Lesuis about former members of the Suriname Student Union. Artist Hedy Tjin created four colourful murals of prominent figures from this period.

‘Agitator’

The eve of the exhibition on the Leiden rediscovery of Anton de Kom has stirred up memories for Paul Day. The 83-year-old Leiden resident was close to the action as a member of the Suriname Student Union in the late 1960s. Day was also in the University Library when Rubia Zschüschen found the forgotten book by the Surinamese writer and freedom fighter.

That discovery prompted the scores of Surinamese students in Leiden to change their perception of De Kom. Day: ‘At school, we had been taught that he was an agitator. Then we discovered that he had fought tirelessly against discrimination, poverty and injustice. In 2020, he even earned a place in the Canon of Dutch History.’

In the Surinamese Student Union, Day – a guitarist and songwriter – was mainly active in the cultural field. Others retyped We Slaves of Suriname page by page. Day helped with collating the mimeographs. He also selected poems from De Kom’s manuscripts for a poetry collection, which was published in 1973 under the name Strijden ga ik (I Will Fight). ‘It is precisely that militancy that I find so striking.’

Day believes he still has a mimeographed copy from that period somewhere at home. But before he can look around, duty calls. Even at his advanced age, the former Socialist Party councillor is still working as a postman, as the documentary at the exhibition shows.

Text: Tim Brouwer de Koning