Looking over the shoulders of medieval readers

What did medieval scholars think of the books they read? In her inaugural lecture on 12 January, Professor Mariken Teeuwen talked about the texts they wrote in the margin. ‘You come across serious things, misery, but jokes too and even music.’

Since March last year, Mariken Teeuwen has been Professor by Special Appointment of Script Culture in the Middle Ages at the Institute for History at Leiden University. She specialises in early medieval books: from the period 500-1500. These were handwritten, often in Latin, on parchment.

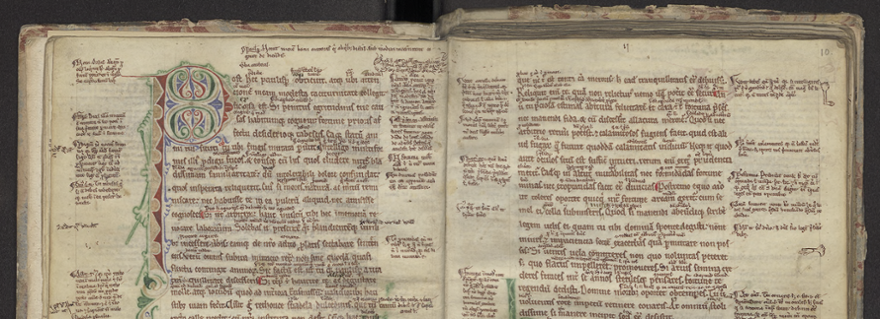

Many of these books contain traces of the readers of that time. They wrote a lot of comments in the margins, margin notes or ‘marginalia’. Most of the authors and readers were monks.

Real puzzle

Liturgical books, which were often beautifully decorated with gold and beautiful miniatures, do not contain many notes, Teeuwen says. ‘Some books are meant to sit nicely on a lectern. To me, the books that people worked with and contain the most marginalia are most interesting.’ These were mainly about philosophy, science and the arts.

Deciphering the marginalia is bit of a puzzle and it takes considerable knowledge and experience − as does establishing when and where the comments were made. ‘Writing developed in a certain way during the Middle Ages. So the shape of the letters gives you information.’

Naked woman

Personal things sometimes pop up among all that knowledge. These can be complaints such as: ‘I’m cold, my fingers are cramped, I’m hungry’. And sometimes readers give their opinions: ‘This master is wrong’ or: ‘This is beautiful. I have to remember it.’

‘You see people from the distant past at work.’

Psalms were sung all day long in monasteries, Teeuwen says. ‘So the writers had their heads full of melodies and these sometimes end up in the margins of a book on a completely different subject.’ Another fun find: in a book on ancient logic, the initial letter is decorated with a naked woman on top of a monk, with blushes on the cheeks of the couple caught in flagrante.

Fantastic feeling

When asked at parties what makes medieval manuscripts so fascinating, Teeuwen says, ‘You are holding a handmade object that is hundreds of years old. These books give you a huge historical thrill. It’s like looking over the shoulder of the person who created or read them. So you see the people from the distant past at work. That is a fantastic feeling. You could compare it to an archaeologist discovering treasures during a dig.’

There are around 5,000 to 6,000 early medieval manuscripts in the public collections of libraries in the Netherlands. Leiden has the largest collection. ‘If you are interested in the early Middle Ages, Leiden is a treasure trove.’

You can get an idea of how manuscripts travelled between European monasteries and cities.

From monastery to monastery

Teeuwen is also a researcher and head of the Digital Editions research group at the Huygens Institute (Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW)). She and her colleague Irene van Renswoude have started building a national portal for digitised medieval manuscripts in Dutch collections.

A huge change is underway in the field of manuscript studies, she says: over the past 20 years, more and more medieval manuscripts have become available online. ‘That has caused a tremendous development in the study of these. Digital methods mean you can compare them much faster and on a much larger scale.’

For example, to determine where, by whom and in what period the book or note was written. Or to get an idea of how manuscripts travelled between European monasteries and cities. ‘It’s only now when, at the click of a mouse, we can see all those original manuscripts digitally on the screen that we can see how much material there is in the margins.’

Mariken Teeuwen will give her inaugural lecture ‘Parchment Persons. The stratigraphy of the medieval book’ on 12 January.

Text: Thessa Lageman

Image: Manuscript from the 12th century containing the Latin text of Boethius’ on the Consolation of Philosophy. The manuscript was annotated by readers and students in the 13th and 14th centuries. Leiden, UB, BPL 144, ff. 9v-10r (Digitale collecties)