The archaeology of face masks: ‘Face masks layers will be a huge help for future archaeologists’

From one year to the next, face masks have started to appear in the environment. As the masks are discarded, they end up in the top soil, in sediment layers, and in refuse heaps. In a couple of generations archaeologists will study the layer that has already been labeled the Face Mask Horizon. Current Leiden archaeologists have already started laying the groundwork for their future colleagues.

This article was the 2021 edition of the Faculty's April Fool's Joke. Which is not to say that the study of face masks by future archaeologists is not something worth considering.

Face mask depositions

We will not rid ourselves of face masks any time soon, geoarchaeologist Irini Sifogeorgakis notes. ‘According to the Marine Environment department of Belgium’s Federal Public Health Service, disposable face masks take up to 450 years to decompose. For some environmental activists this might sound like alarming news, but geoarchaeologists around the world have started to rub their hands together.’

Indeed, face masks now disposed in the environment can serve as a sure way to date deposits by future archaeologists. ‘These distinct face mask layers will be a huge help for future colleagues!’ Sifogeorgakis exclaims. ‘Yes, a lot of human waste has been a source of sedimentation during the last decades but you cannot determine the exact dating using a straw. Already many experimental projects have been set up to determine the exact taphonomy of face masks.’

Ritualistic behaviour

Colleague Riia Timonen is investigating face mask distribution patterns. ‘Over the past year, I have used intensive reconnaissance methods to record the appearance of abandoned face masks in the metropolitan area of Leiden.’ She found a pattern with remarkable clarity. ‘Face masks cluster around modern subsistence activity areas such as supermarkets, slagerijen, and fromageries. Thus, there is a strong relationship between food acquisition and face mask abandonment.’

Timonen’s research suggests that the face mask abandonment takes place after the food acquisition is completed. ‘The abandonment itself seems to occur as a rite of freedom individualistic self-liberation from elitist/governmental rules. The presence of food during this rite suggest that it often initiates a more complicated chain of ritualistic behavior – a domestic feast.’ Timonen is thrilled to further explore this promising method to examine the mysterious behavior of modern humans.

Intentional abandonment

Valerio Gentile also study intentional abandonment, but he reaches slightly different conclusions. ‘The discard of such a quantity of specimens it is often explained by scholars as a combination of material and economical aspects: the abundance and availability of these items, together with their single-use nature, automatically discouraged long term accumulation behaviors.’ However, Gentile has found this explanation to be too simplistic. ‘Random discard patterns are not meaningless when predetermined discard points, such as bins, are also present in the landscape.’

Now this is an interesting factor, especially considering the early 21st century notions of sustainability. ‘One can postulate that what was culturally perceived as the ‘right ending’ for these face-mask was their discard into the proper bin,’ Gentile explains. ‘Although many of these items were indeed disposed of in such a way, thousands of others were not. There must have been rules prescribing which face-mask was to be discarded in a waste container while another had to be deliberately deposited on the ground.’

Even stranger, many cases in which deposited face-masks have been found only a few steps away from a waste container. ‘Such an apparently irrational performance can only be explained as ritual practice embedded in unfamiliar cultural norms. Further investigation of these practices might help us better understanding the otherwise puzzling mindset of this time.’

Styles and expressions

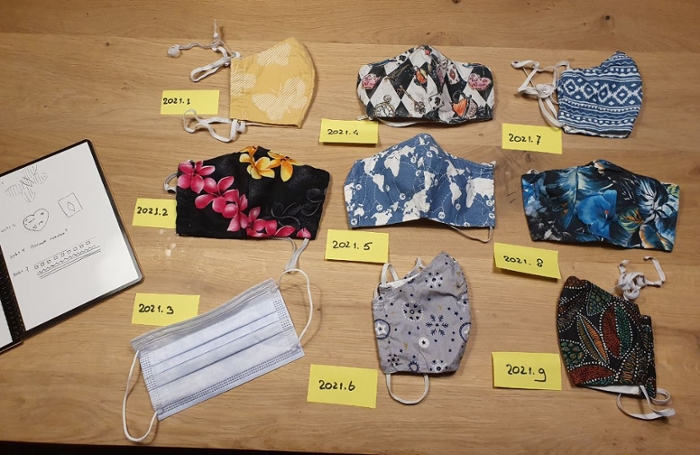

Marlieke Ernst notes that style is an important part of any archaeological study, as it is often seen as a form of communication and information transfer. ‘This makes us think about the expression of identity through style in the face masks. The majority of the masks find in the streets are plain disposable blue or black ones (2021.3). But we see all sorts of expressions in the re-usable masks.’

Ernst points at Sample 2021.6, which features Christmas-themed figures. ‘This makes us think that this person was a Christmas-lover wanting to express holiday-joy. A common theme is flower/nature expressions, suggesting that these people were rooting for a greener world. Sample 2021.5 really makes us wonder; did this person secretly convey escape routes to others? Or is it showing the way the virus spread as a warning?’

Some styles are completely puzzling the experts. ‘If anyone could spread light on 2021.4 with this weird combination of keys, locks, rabbits, cookies, play cards and tea cups, please let us know.’

Face masks in satellite imagery

Wherever there is big data, the digital archaeologists are involved. Wouter Verschoof-van der Vaart is adapting computational approaches that have been developed to automatically detect and map a wide variety of archaeological sites and artifacts in images gathered by satellites and aircrafts. ‘These methods have hardly been used in contemporary archaeology. Therefore, in light of the recent pandemic, we are now developing new computer models to not only detect prehistoric barrows and Roman pottery fragments but also contemporary face masks in satellite imagery.’

This is an important step in the study of face mask distribution patterns. ‘The systematic mapping of these face masks on a landscape scale can give us lots of information on the movement and depositional practices of modern humans in the urban landscape and offers many possibilities for contemporary landscape archaeology.’

Transmitted knowledge

At the Laboratory of Material Studies Erik Kroon is investigating the face mask’s technology. ‘Making a facemask is not an innate skill: it comes with years of training, specialised equipment, and knowledge about raw materials. All of this knowledge is transmitted within societies.’

By studying the production processes of face masks, this ancient knowledge can be reconstructed and how it developed over time. ‘Do we, for example, see mass production in a few specialised contexts?’ Kroon muses. ‘Or do people improvise the general shapes and styles of facemasks within their own technological repertoire? How do these different modes of production relate to each other over time? Can we correlate technology with variables such as style, place of deposition, and use?’

Ultimately, solving these questions helps us to understand the economy of knowledge in these bygone eras. Or last week.

Face masks to feature in education curriculum

During this Covid-19-crisis it is extremely important to keep an eye on the developments within the job market. As our researchers show, we expect the archaeology of the future to have a new area of study.

To adapt to the new situation we are currently working hard on developing new learning lines and consequently implement them in our curriculum, so that the future generation of archaeologists will be well prepared with the necessary skills to study all aspects of the artefacts identified as face masks. Already in the first year our students will learn in the course Material Studies to analyse face masks in relation to cultural identity, societal status, as well as behavioral patterns. In the course Field Techniques the automated detection of face masks will be one of the learning objectives of our students. Our students therefore will be trained from day one in the wide variety of new skills that will be asked from them in this face mask dominated archaeological job market.

Just one more thing

Even though future archaeologists will be very grateful for the intentional deposition of your face mask, we would like to ask you to throw it, ritualistically, in the bin.

Naturally, all face masks under investigation have been handled with care.