Festival showcases anthropology students’ work: scope of visual ethnography is widening

Visual ethnography has become an integral part of anthropology in Leiden. The students from the master’s specialisation will present their work at the LUVE festival on 8, 9 and 10 October. ‘For a film you have to negotiate with your research participants.’

Associate Professor Mark Westmoreland begins by setting things straight: visual ethnography is no longer about film and photography alone. Nowadays it is a multimedia discipline. One student built an installation for her master’s degree and another drew a graphic novel. And there’s the internet too, with all the opportunities that offers. But fieldwork continues to form the basis of the discipline. And that means: looking and listening attentively.

Most anthropology students like to go abroad, but that wasn’t possible during the pandemic. This led to original and creative projects, which can be seen at LUVE Festival from 8 to 10 October in De Buurt in Leiden. LUVE stands for Leiden University Visual Ethnography.

How and why

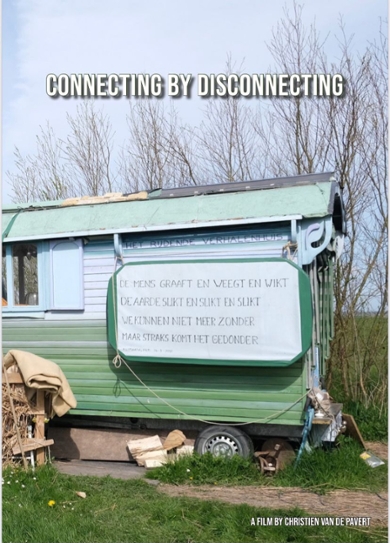

Christien van de Pavert conducted research into people who live off grid, which means consciously doing without certain so-say essential utilities. In the case of Van de Pavert’s research this meant electricity. Alongside her thesis she made a 30-minute film. Anthropology as a science is observing and participating, and exploring how people do things and why they do them. The ideological aim of the off-gridders proved to be a sustainable lifestyle. It wasn’t difficult to find participants once Van de Pavert had discovered the lively Facebook group where they swap tips. ‘Off-gridders generally live in small home –a caravan, tiny house or a camper. But it can also be a “regular” flat.’ For the film Van de Pavert also wanted to join in the participants’ daily lives. She can be seen helping dig a vegetable patch, for instance.

‘Old-style’ thesis

Alongside the film, or other medium, the students wrote a 10,000-word master’s thesis. Van de Pavert: ‘This covers the regular elements of scientific research.’ How do the two complement each other? Van de Pavert: ‘The film is less about the arguments why people try to live off grid. It’s more about their search. You have to come up with your own interpretation. You do find the arguments in the thesis, though. That’s more explicit. For the film you also have to negotiate more with the participants. We discussed together what to show and how. As a researcher you therefore learn more about what a participant does and doesn’t consider important and why. That helps answer your research questions, which also helped me achieve what I wanted: for it to be a joint project.’

Auto-ethnography

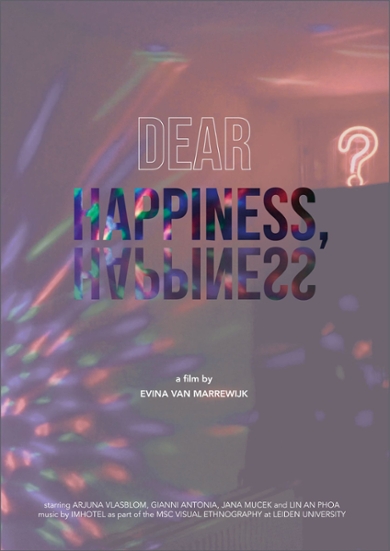

Evina van Marrewijk also chose to make a film, but then from an auto-ethnographical perspective: about her own somewhat latent feeling of dissatisfaction as a millennial. That dissatisfaction arose from the idea that society gave her that she could chase her dreams: ‘The possibility to chase your dreams also gives rise to an inherent pressure to succeed. You’re expected to have dreams and to realise them.’ Evina likes lots of things, such as research, urban dance and hanging out with others. But she felt she had to choose because our busy world offers little space for doubt and exploring different paths. Students have to complete their degrees within a set period and then society expects you to be successful at something. After peeling away the layers, she discovered her main question was: what actually makes me happy? She found four peers and in her film they investigated what happiness means for millennials. The question became all the more pressing with the pandemic: ‘When I started filming you could only see one person and there was a curfew. Then I really was left to my own devices.’

Anthropological context

The four participants could identify with Van Marrewijk’s questions: ‘Their discourses were like mine. One of them lost her job and experienced how her happiness was linked to her work. My research encourages people to see happiness as something that is always changing shape instead of something that is linked to certain factors, such as work and success. It implicitly invites them to start a countermovement.’

When asked if this is still anthropology, Van Marrewijk says: ‘My supervisor kept on hammering it home: don’t forget the anthropological context. But I soon discovered that anthropology offered plenty of ways to tackle the topic.’ It was about the how and why. Her final products resulted in a grade of 9, as well as more peace of mind and the realisation that she doesn’t have to choose. So a psychological effect after all.

Different way of looking and listening

Associate Professor Westmoreland, who is also coordinator of the master’s track, takes his students to Volkenkunde Museum and gives them an assignment: don’t use a map but instead follow your nose (or rather: your eyes and ears) and make a drawing of one object. You don’t have to be able to draw. This is about looking carefully. He also walks through Leiden Centraal train station with his students. ‘I ask them to listen attentively: what kinds of thing do they hear? We take sound for granted but we shouldn’t. The students are surprised by what they hear in the station if they listen properly.’ Students say that the two methods change how they look and listen, even in environments that they think they know well.’ They exchange their unseeing eyes and unhearing ears for ones that see and hear keenly, and take these skills with them, also to later jobs at cultural and development organisations and NGOs, for instance. Westmoreland adds that in the professional sphere visual ethnography is a good way to introduce the human dimension to fairly abstract problems.

Modernise and widen scope of visual ethnography

Westmoreland comes from the United States and studied there before working in Lebanon and Egypt. He has studied how activists capture their message in pictures that they upload to YouTube. He came to Leiden six years ago to update visual ethnography and widen its scope to new media.

And then there’s the degree

Both students say that the master’s was fun and valuable, but it was difficult too. It’s a lot of work to record your research in two ways in one year and also to learn all the different techniques for the new method. And to have to do lots of assignments too. But they are both satisfied and are looking at the opportunities to gain wider attention for their film, at other festivals, for instance. But first their own festival, which they are organising themselves, and on the day after – 11 October – their master’s degree ceremony.

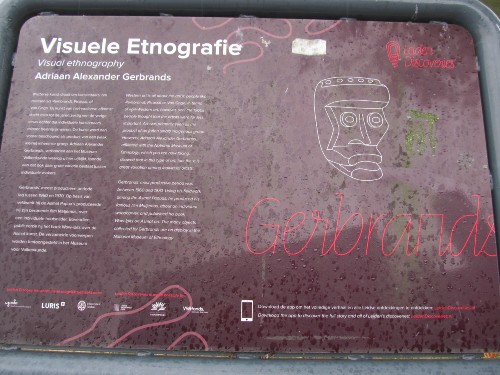

Adriaan Gerbrands (1917-1997) was the founder of visual ethnography. He was a curator and deputy-director of Volkenkunde Museum for 20 years and a professor of cultural anthropology. This combination produced the new academic discipline of visual ethnography. In the early 1960s Gerbrands was a pioneer in combining ethnographic film and material culture studies in order to translate cultural differences in aesthetic production. He also developed and was a strong advocate of a theoretical framework for the new discipline.

This Leiden Discoveries information sign about visual ethnography and Adriaan Gerbrands is opposite Museum Volkenkunde, the National Museum of Ethnology, on the corner of Morssingel and Rijnsburgerbrug.

Text: Corine Hendriks

Photos: @Simone Both and Leiden University