Tackling climate change with the ground beneath our feet

Soil ecologist Emilia Hannula has been awarded a Vidi grant by NWO to examine how soil could become a promising ally in combating climate change and improving biodiversity. ‘Soil creatures might be invisible’, she says, ‘but they play a huge role in creating a healthy environment.’

There is more carbon globally in our soils than in the air or vegetation. That means the ground beneath our feet plays a huge role in preserving the environment and limiting climate change. Depending on how we treat it, soil can be a carbon source or a carbon sink.

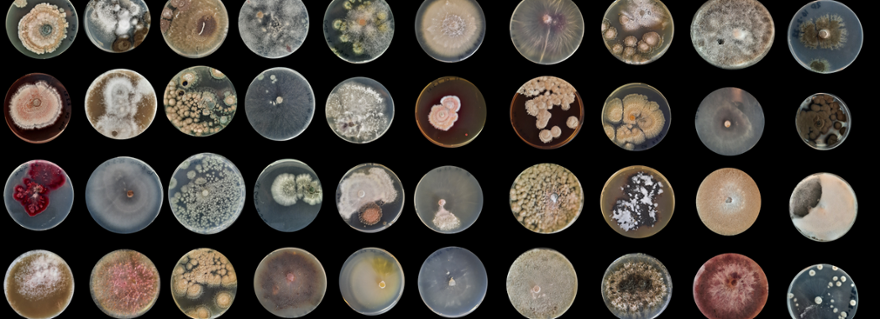

‘Still, quite a lot about the soil is unknown’, says Hannula, assistant professor at the Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML) in Leiden. ‘It's not like birds and animals that have been studied over and over. The creatures in our soil are invisible and go largely unnoticed.’

Fascinated by an invisible world

Hannula is fascinated by this invisible world. After having studied soil fungi for 15 years, she has now been awarded a Vidi grant worth 800,000 euros by the Dutch Research Council NWO to deepen her research. It allows her to conduct five years of research and makes it possible to hire a doctoral and postdoctoral researcher.

With the new funding, Hannula, originally from Finland, will study how soil creatures and fungi operate and work together. ‘In order to better understand how we can use soil to our advantage, we need to know how the communities that live in it are composed’, she says. ‘We want to find out how these soil creatures and fungi function and how this varies between different types of soil, from an urban to an agricultural and forest environment.’

How various soil cultures influence each other

Hannula will specifically look at Dutch soil, both in the natural environment and in controlled conditions. ‘In the lab, we can observe how fast the fungi in the soil grow and how much biomass they gain’, she says. She is particularly interested in how various soil cultures influence each other. ‘We experiment with adding bits of one culture to another and see how they interact.’

The researcher has developed an pioneering technique to monitor how soil captures CO2. ‘By using a stable isotope, the carbon becomes a sort of marker’, Hannula says. Compare it to a contrast agent that is used in MRI scans to improve the visibility of parts of the human body. The technique allows Hannula to track precisely where the carbon ends up in the soil.

An ally in combating climate change

What makes these new discoveries so exciting is the fact that soil could become a promising ally in combating climate change and improving biodiversity. ‘Eventually, we will be able to use soil to 'steer' the natural system’, Hannula says. ‘Not just by restoring areas that have been damaged by human activity, but also by potentially turning some soils from a carbon source into a carbon sink.’

That doesn't require a total overhaul of existing natural systems, Hannula reassures. ‘It can be quite simple measures, such as adding wood chips to agricultural soil or improving the biodiversity of trees in a forest.’

Text: Samuel Hanegreefs