Uzbek mathematician refines world-famous theory: ‘So many things are connected’

Predicting the collective behaviour of systems, like a large group of people electing one of the parties, is no easy task. But there’s a theory that scientists have been using for decades to do just that: the theory of Gibbs measures. Last week, mathematician Mirmukhsin Makhmudov earned his PhD for refining this very theory.

Makhmudov’s research in his dissertation ‘Gibbs States in Statistical Mechanics and Dynamical Systems’ focuses on how systems interact. ‘Think of elections, where everyone has their own opinion. Or a piece of metal, where atoms can become magnetised. In both cases, there are local interactions. Those interactions can influence the entire system,’ he explains. ‘For mathematicians, it doesn’t really matter whether we’re talking about people or atoms of iron.’

This kind of theory can be applied across many fields, from biology and linguistics to IT and sociology.

Three steps, five research projects

At the Gorlaeus Building, Makhmudov speaks enthusiastically about his discoveries, occasionally sketching simplified versions of his research on a whiteboard or jotting down formulas. He might sound like someone who stumbled upon something by chance, but that’s certainly not the case.

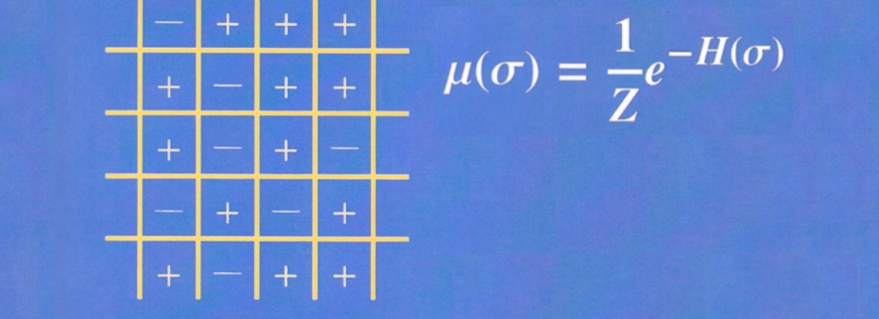

He refined the Gibbs theory in three clear steps, using insights from five different research projects he contributed to. His first focus was on the various ways of defining what’s known as a Gibbs measure, a way to describe how likely it is for a system to be in a certain state.

For the entrance exam to the master’s programme, I got the highest score. That means you get a full scholarship. The lower your score, the more you have to pay yourself.

A love of maths discovered early on

Makhmudov talks about his academic journey with the same ease he brings to his research. He was born in the Khorezm region of Uzbekistan, far from the capital Tashkent, and discovered his love for maths at a young age. He scored so highly on his university entrance exam that he was offered a government scholarship. During his undergraduate studies, he won one mathematics competition after another.

‘For the entrance exam to the master’s programme, I got the highest score,’ he says. ‘In Uzbekistan, that means you get a full scholarship. The lower your score, the more you have to pay yourself.’

Back to the PhD research. In the second part of his dissertation, Makhmudov studied what happens when a system of interacting particles is split into parts. He proved that, under the conditions he examined, the Gibbs states before and after the split remain absolutely continuous with respect to each other.

While working on this, he made another interesting discovery: the problem turned out to be closely related to a well-known result in mathematics, the Perron-Frobenius theorem. Behind the scenes at Google, this theorem plays a key role in the PageRank algorithm. ‘It was exciting to see how so many things are connected,’ says Makhmudov.

I wasn’t sure what to do, but my boss said: why not do both?

Scouted by Uzbekistan’s central bank

Unexpected connections aren’t just part of his research, they’re also a feature of his career. Before he even started his master’s with a scholarship, he had already been scouted by Uzbekistan’s central bank. ‘I wasn’t sure what to do, but my boss said: why not do both?’ And so he did. ‘It was a bit of an unusual setup, but in the meantime I was promoted twice at the bank,’ he says, laughing.

As if that weren’t enough, he added a third part to his dissertation: a study of the multifractal properties of so-called Gibbsian systems, especially those influenced by rare, extreme events. ‘These events almost never happen, but when they do, they matter a lot.’

From Uzbekistan to Trieste to Leiden

A dissertation that’s really three in one, but for Makhmudov, that’s nothing new. After graduating as chief economist at the central bank, he was immediately offered a fellowship at the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste. There, he wrote his diploma thesis and, thanks to a tip from a professor friend, applied to the PhD programme in Leiden. He was admitted in September 2021.

During his PhD, the Uzbek mathematician taught courses and presented his work at international conferences. The crowning achievement: receiving his doctorate on 2 September. And now? ‘I’m not sure yet,’ he says. ‘ I have a job offer in China, from the Shanghai campus of the New York University starting in January 2026. I also have several other applications still under review. I guess the first step is returning my Leiden University laptop.’