Daan Weggemans: 'Digital security is not just for specialists'

Within a single generation, the digital world has changed completely: from a technical niche for ‘nerds’ to a reality that affects everyone. Cyberattacks, data breaches and system failures can disrupt essential social processes. How can we ensure that our society remains digitally resilient?

From convenience to vulnerability

'From the moment we wake up and reach for our phones to the time we order groceries online, everything that offers convenience also makes us vulnerable in new ways,' says Daan Weggemans, Assistant Professor at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs.

That vulnerability only becomes visible when something goes wrong. 'For example, when air traffic comes to a standstill because of an error in a software update — that’s when you see just how deeply digital systems are woven into our daily lives.' According to Weggemans, the causes of digital disruption can broadly be divided into two categories: accidents and attacks. 'Whether the incident is malicious or not, in both cases the impact can be enormous.'

Cybercrime as a business model

Where money circulates, criminals find ways to profit from it. ‘In the past, there might have been a few hackers extorting individuals,’ Weggemans explains. ‘Today, cybercrime has developed into organised crime with major economic and social consequences.’

Criminal networks operate like businesses, complete with products and services. Consider ransomware: software that locks files until a ransom is paid. ‘A professionally organised underground market has emerged,’ he says. 'On the dark web you can buy almost anything – from ready-made viruses to access to specific systems or data.' The dark web is the unindexed, anonymous layer of the internet where criminals trade services and data without revealing their identities.

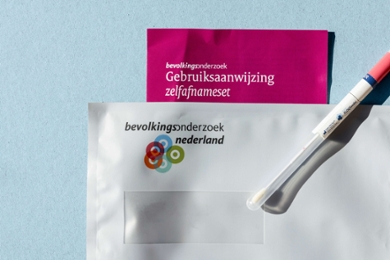

The effects of digital attacks are felt across all sectors, from universities and companies to hospitals and government bodies. A recent example is the hack on the laboratory that conducts research for the national cervical cancer screening programme, in which large amounts of personal data were stolen. ‘Such incidents directly undermine public trust in government and healthcare institutions,’ says Weggemans.

The effects of digital attacks are felt across all sectors, from universities to hospitals and government bodies. A recent example is the hack on the laboratory that conducts research for the national cervical cancer screening programme, in which large amounts of personal data were stolen. ‘Such incidents directly undermine public trust in government and healthcare institutions,’ says Weggemans.

Not always malicious, yet highly disruptive

‘Sometimes a simple human error is enough to bring the world to a standstill,’ Weggemans notes. ‘A few lines of faulty code or malfunctioning hardware can suddenly disrupt critical communication or infrastructure.’ He points to incidents such as the global airport disruptions caused by a malfunction in CrowdStrike’s software. ‘There was no malicious intent behind it, yet the impact was immense. It shows how dependent we are on digital infrastructure.’

That is why he regards digital security as a layered issue. 'It is not just about technology, but also about human behaviour, governance decisions and legal frameworks. How is digital security organised? Who bears responsibility? And what happens when something goes wrong? How do we create a resilient society?'

My colleagues, Bibi van den Berg, Professor of Cybersecurity Governance, and Cristina del Real, Assistant Professor, recently advocated the principle of security by design: systems that are secure from the outset and take into account users’ limited digital literacy. According to them, this represents an important part of the solution: 'Digital security must be accessible and intuitive. Users should be able to rely on it without having to think about it constantly,' they emphasise. 'We cannot expect every citizen or small organisation to possess all the specialist knowledge required.'

Balancing openness and security

The Netherlands has a strong ecosystem in the field of digital security, Weggemans emphasises. 'There are increasingly good examples of public-private cooperation between government, police, industry and knowledge institutions. At the same time, it remains a young and fragmented landscape: responsibility is spread across many parties, which can make things complex.'

New technologies such as AI and quantum computers also bring new risks. 'The computational power of quantum computers will put existing security systems under pressure. Think of passwords that could be cracked in seconds,' says Weggemans. 'But not every development is immediately as threatening as science fiction suggests. These changes call for new standards, regulations, and, above all, knowledge among administrators and policymakers to deal with them effectively.'

‘Digital security belongs on every boardroom agenda.'

Digital security demands leadership

Digital security belongs on every boardroom agenda, Weggemans believes. ‘It affects every organisation, from local authorities to national ministries. Cybersecurity is a governance issue.’ Yet many organisations only take action after an incident. ‘That is too late. You should not start thinking about digital security once your systems have already gone down.’

Knowledge development is therefore essential, particularly for professionals outside the technical domain. ‘We cannot expect everyone to become a programmer,’ he says. ‘But policymakers, legal experts and executives must understand how digital risks work – and how their decisions can influence those risks.’

The future calls for digital minds

The demand for professionals with digital expertise is growing rapidly. Governments, security agencies and companies are seeking people who understand how technology, policy and law intersect. ‘That’s why, as a university, we invest in programmes that connect academic knowledge with professional practice,’ says Weggemans.

As director of the new bachelor’s programme Cybersecurity and Cybercrime, he experiences this urgency every day. ‘Interest is high, and organisations are already asking when students will graduate. They need people who understand technology and can navigate its governance context.’

‘Technology is advancing at lightning speed,’ Weggemans concludes. ‘But ultimately, it is people who decide how we use it. The choices we make today – in policy, design and education – will determine the digital resilience of tomorrow.’

In January, the Centre for Professional Learning will offer the Cybersecurity Programme. One of the lecturers is Daan Weggemans, Assistant Professor and researcher at the Institute of Security and Global Affairs (ISGA).

The Cybersecurity programme

The CPL’s Cybersecurity Programme examines these digital risks. Over four intensive days, participants gain insight into the technical, legal and administrative dimensions of digital security. ‘They learn to speak each other’s language and to see how policy, organisation and technology can either reinforce or undermine one another,’ says Weggemans. Participants come from a wide range of sectors – government, healthcare, infrastructure, justice and business. ‘That diversity is valuable,’ he adds. ‘A lawyer, a policy adviser and an IT manager each view the same problem differently. Bringing those perspectives together fosters understanding, collaboration and practical capability.’

More information and registration