Algebra, activism and asbestos: the curious life of Fred Rohde

As a mathematician, Fred Rohde (1948) explored the world of numbers. As a photographer, he captured demonstrations. And now he’s reconstructing his mother’s wartime story – an extraordinary tale of her stay with an Austrian family, the inventors of asbestos cement.

Step into Fred Rohde’s intimate studio on Nieuwe Rijn in Leiden and you step straight into his artistic and personal world. On the wall are childhood photos of his mother, his own artistic photos and the vibrant work of his wife, artist Molly Ackerman.

Abstract world

‘Going to university was a huge step,’ Rohde reflects. ‘I was a real first-generation student. My parents both started work at 14. The university was a whole new world for me.’ An inspiring maths teacher at school gave him the confidence to take that step. It was 1966, and in Leiden, students were also beginning to demand more representation. Later an activist, Rohde was a diligent student at the time. ‘I took a very systematic approach to my studies, really threw myself into them. With maths, you have to understand every tiny detail – otherwise nothing works. That’s what I liked about it. The abstract world of maths fascinates me.’ He also studied physics and astronomy.

Social awareness

To unwind, he joined the Catena student association. In 1969, students occupied the Academy Building for weeks, demanding more democracy. Rohde was intrigued, but he didn’t join in. His social awareness grew later, after graduating in 1976. ‘As a young maths teacher, I began to be frustrated with the authoritarian older generation of colleagues at my school. I joined the Socialist Party and became active.’

-

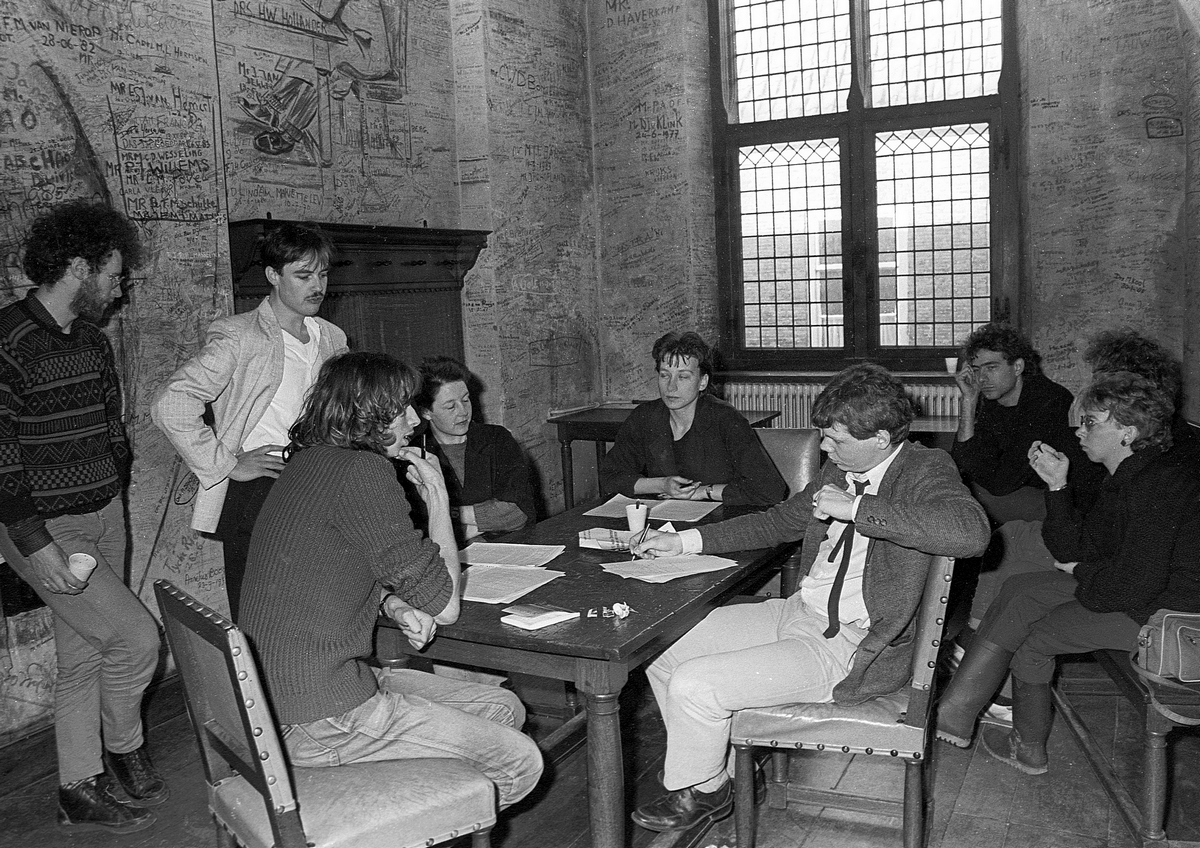

In 1969 Rohde wasn’t present at the occupation of the Academy Building, but in 1985 he was. Intense deliberations in the Zweetkamertje. Photo: Fred Rohde. -

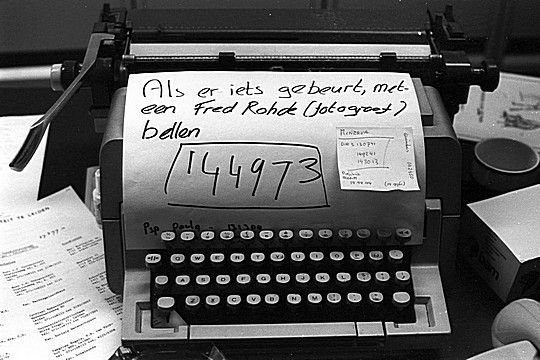

Protest against a visit by Minister Deetman in 1985. Fred Rohde -

'If anything happens, call Fred Rohe (photographer)'

Change of course

Around the age of 30, he began to question whether he wanted to stay in teaching. ‘I had an early midlife crisis and everything, including my private life, was turned upside down.’ He found temporary work at the Ministry of Education, where his job was to answer letters. He hadn’t found his calling, but the proximity to Binnenhof was a huge advantage. ‘During breaks, there was always something happening. I photographed demonstrators or politicians almost daily and spent my day off in the darkroom. That how I became a photographer.’

Student protests

Rohde started taking photos for the Leiden Student Union. ‘Then I closely followed and photographed the student protests in the 1980s, so I experienced an occupation of the Academy Building after all. Great to see how passionate those students were.’In early February 1985, Leiden students demonstrated for days against Education Minister Deetman’s plans for a new student funding system. They were strongly opposed to Deetman speaking at the university’s Dies Later, he worked for the Leidsch Dagblad newspaper and tattoo magazines, also writing stories for them.

Asbestos

He is now putting the finishing touches to his book ‘Oorlog en Eterniet’, which takes us back in time once more. For the Socialist Party, he organised campaigns against injustices – including one targeting a building supplier that continued selling asbestos cement sheets in the 1970s long after the health risks were clear. ‘The campaign attracted national attention and was a turning point in the fight against asbestos. And that’s when the penny dropped for me personally.’

His mother’s war

His mother often spoke about her wartime experiences. With Rotterdam in ruins, Dutch children were invited to Austria to recuperate. Through her school, his mother stayed with the renowned industrial and aristocratic family of Hans Hatschek. Hans was the son of Ludwig Hatschek, the inventor of Eternit – asbestos cement. ‘My mother was happy there. She even returned to Austria in October 1944 to work in their factory. Luckily, she protected herself by tying a cloth around her mouth and nose, so never fell ill. She lived to the age of 90.’

A different light

But the story is complex, he stresses. The Hatschek family had Jewish roots and had converted to Catholicism just a generation earlier. Austria had been annexed by Nazi Germany, making his mother’s time there morally ambiguous, says Rohde. ‘I spent 20 years researching it. I’ve found letters from that period that no one had ever looked at. They cast a different light on this famous Austrian family.’

He is still working on the book, so he doesn’t want to give away too much. He plans to self-publish ‘Oorlog en Eterniet’ (War and Eterniet) later this year. ‘I expect it to cause quite a stir. This story mustn’t be forgotten.’

Value of a degree

At the end of the interview, Rohde returns his studies. Hasn’t he taken a completely different path from mathematics? It depends on how you look at it, he says. ‘I taught for over 40 years to pay the bills. Mathematics taught me to break down complicated problems until I understand them and to explain that clearly to others. I’ve taken the same approach to writing my book. Only this time, it’s taking me twice as long as my degree did.’

For more information about the book, mail Fred Rohde.