Gorillas abducting women leads to new art history

Two statues of gorillas abducting women: they were what led PhD candidate Dick van Broekhuizen to write a new type of history of nineteenth-century sculpture. ‘If you view nineteenth-century art history from a less narrow perspective, the narrative changes completely.’ PhD ceremony on 21 June.

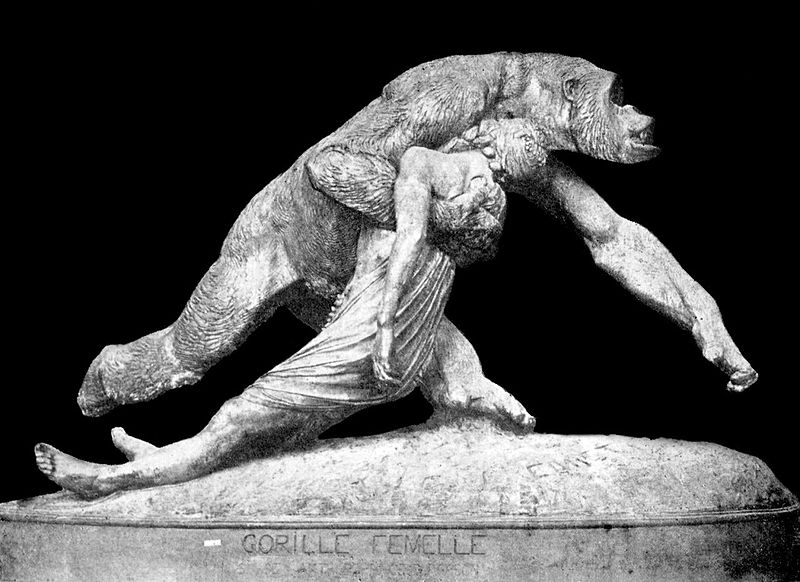

A few years ago, a sculpture by French artist Emmanuel Fremiet was exhibited in the Beelden aan Zee museum. The subject was a gorilla carrying off a woman. Van Broekhuizen, curator at the museum, became intrigued by this sculpture as well as by an earlier version of it. He wondered how the artist was able to sculpt a true-to-life gorilla in 1859, when the species only started to become known in Europe in 1847. He also wanted to know how these statues fit into the larger history of nineteenth-century art.

Primitive conservative kitsch

‘When we look at nineteenth-century art, we mainly focus on paintings,’ says Van Broekhuizen. ‘Almost every young girl’s room was decorated with the landscapes of Sisley or the dancers of Degas, but virtually nothing is known about sculpture. In the twentieth century, the sculptor Rodin was idolised. All the others were dismissed as primitive, conservative kitsch.’

As a result, there is almost nothing to be found in art history research about Fremiet’s sculptures: he is only mentioned a few times in a scientific work in the twentieth century. Even the nineteenth-century biographies of the artist, dating from a time when he was still popular, shed little light on this. These often romanticised biographies mainly explain why Fremiet was able to depict gorillas so early on. ‘He does not have an art school background, but he was brought up surrounded by science. ‘He often worked for zoos, where he sculpted prehistoric animals, among other things,’ Van Broekhuizen explains. ‘That’s how he came into contact with dead gorillas that were shipped to Europe so early.’

From nature to art tradition

Early on, Fremiet’s gorilla sculptures also seemed to be a faithful representation of nature. The first sculpture shows a running gorilla dragging along an African woman from Gabon. ‘Fremiet presents it as a work of art, but in reality it’s very much in the tradition of a museum such as Naturalis: a natural science museum where an artist’s impression depicts what an animal is like in real life,’ says Van Broekhuizen. ‘Fremiet’s sculpture is a colonial fantasy, but at the time it was viewed as very realistic. That’s why the public thought it was frightening. They were worried that this could happen to them if they went out into the wild.’

Thirty years later, however, Fremiet takes a different approach. He presents a much larger sculpture of a standing gorilla with a struggling white woman in his arms. Van Broekhuizen: ‘That sculpture is closer to an Abduction of the Sabine Women, placing it in a completely different discussion. The focus shifts from natural history to art history.’ The theme of the abduction of women was already popular in the Renaissance and it experienced a revival in the nineteenth century. ‘When Fremiet adds the gorilla, he is criticising, among other things, the idea that artists have to imitate ancient art. In the nineteenth century, classical art was very important for sculpture, but at a certain point some artists started saying that they didn’t just want to look at ancient Rome, but also at artists from the fifteenth or sixteenth century, such as Michelangelo and Giambologna.’

-

Gorille enlevant une négresse, 1859 -

Gorille enlevant une femme, 1887

The sculpture is therefore part of a debate among artists, but it also plays a role in the larger social debate of the time, in which the nation state is becoming more popular and anti-Semitism is on the rise. ‘A critic wrote a text in which he claimed the sculpture was completely anti-Semitic,’ says Van Broekhuizen. And the gorilla is more often interpreted as the personification of the feared decline or perversion of the nineteenth century. At an exhibition in Munich, the statue was placed next to an equestrian statue of a German general. The message is clear. ‘We think the gorilla is beautiful and we’ll give the French artist a first prize, but we want German artists to work at the same exalted level as that horseman.’

Unique art history

Ultimately, these two gorillas led Van Broekhuizen through all kinds of facets of art history, though he had to expand the traditional skill set he has as an art historian with all kinds of other sciences, such as biology. He views this positively. ‘The sculpture calls for other perspectives, input from other disciplines, from which a completely different art history of the nineteenth century emerges. And there’s the added bonus of an entirely new perspective on the art world in Paris in the nineteenth century.’