In search of hidden voices

Nearly all documents from the 16th and 17th centuries were written by more than one person but attributed to only one author. Professor Nadine Akkerman wants to rectify this oversight in her research on scribes. ‘We have a responsibility to recover all the discrete voices.’

Nadine Akkerman was appointed Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture in 2022 and gave her inaugural lecture on 3 May. The title ‘The Tale of the Manx Cat: Recounting Early Modern Authorship’ referred to a cat described by Virginia Woolf in her influential essay A Room of One’s Own. ‘Woolf looked for women who like her were “true autors” and had written literary works but came to the conclusion that hardly any of her predecessors were such a thing’, Akkerman explains. ‘Those handful she found lacked a certain something. Woolf has Mary, her protagonist, suggest, “what a difference a tail makes.”’

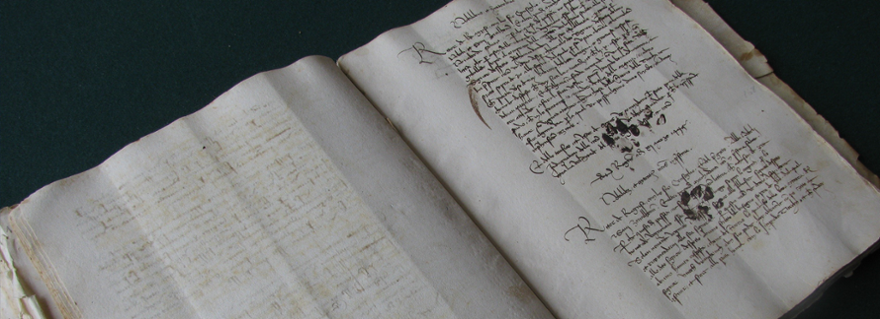

Woolf appears to have been blind to the writers who preceded her in the 16th and 17th centuries. And she was not the only one, says Akkerman. ‘Woolf’s rather damning opinion of women’s writing of the early modern period was the received wisdom for some 50 years. We now know that their primary mode of literary production was in manuscript, that is, handwritten documents. Such female-authored documents were rarely collected, properly catalogued, edited and published.’ Opinion only began to change when, in the 1980s, literary scholars set foot in the archives and university libraries to seek early modern women’s writing.

‘Woolf’s rather damning opinion of women’s writing of the early modern period was the received wisdom for some 50 years.’

Male scribes

Behind these long-hidden voices is often another hidden voice. That is the voice that Akkerman is currently researching. ‘Women in general rarely held a pen in their hands. When the need or urge to write presented itself, they dictated their words to a scribe. Scribes or secretaries, unlike today, were mostly male. Male writers also made use of such mediation to compose their texts. Many texts produced in the 16th and 17th centuries were the result of collaborative enterprises. We have overlooked the figure behind this: the secretary, the penman, the scribe.’

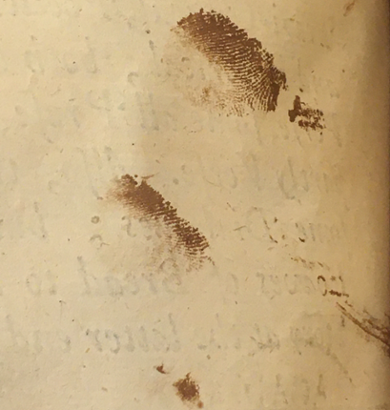

This is a recurrent theme in Akkerman’s academic career: making the unexpected visible, often things that have long been overlooked. Her previous research has included female spies and 17th-century perfume recipes. And now it is the turn of scribes. ‘Scribes,’ she says, ‘could edit texts as they went along, intrusively as well as subtly. With the understanding that manuscripts conceal multiple possible authors becoming commonplace, we must find ways to make sense of these possibilities, and to isolate discrete voices. We have a responsibility to recover these and other invisible actors who, nevertheless, left so many fingerprints behind.’

Signature folds

Akkerman went on to look at the many ways in which these invisible scribes left fingerprints behind. ‘Sometimes literally. We are attempting to understand the making process, not merely to consider the final product.’ She gave the example of letterlocking − the way a document is folded. ‘That can be as telling as a signature when it comes to establishing the identity of the last person to manipulate the letter.’ The sand writers used to blot their ink can also be analysed to determine a document’s origin, as the research of Birgit Reissland shows us, for instance.

Akkerman also uses modern technology for her research. One project she worked on used microtomography and algorithms to digitally unfold and ‘read’ documents that still had their seals intact. But she warns, ‘While digital humanities has been a godsend, we must remind ourselves that digitisation is not necessarily a benign process. Besides its large carbon footprint, preparing documents for digitisation can erase features that might be of use to future generations of scholars – blotting sand that still adheres to the letters is brushed off and paper folds smoothed out, for example. We need to be careful not to destroy material evidence for future generations.

Recording inaugural lecture (in Dutch)

Due to the selected cookie settings, we cannot show this video here.

Watch the video on the original website or